From massacres to markets: how the strategy of godfathers has changed

Check out the article Paolo Pinotti (Scientific director at CLEAN) and Gianmarco Daniele (Executive Director at CLEAN) wrote for La Repubblica, one of the main Italian newspaper.

Since the article is in Italian, we provide a translation here:

Criminal organizations have partly changed their skin in the past 30 years. By drastically reducing the number of murders and using violence in a more strategic and less visible way, they have been able to infiltrate new areas of the country and new economic sectors, without abandoning the illegal trafficking that remains part of their "core business."

The period of Mafia massacres such as the Via D'Amelio massacre in which magistrate Paolo Borsellino and 5 agents lost their lives represented the culmination of the clash between the Sicilian Mafia and the Italian State. In 1991 alone, there were 1,916 murders, 718 of which were mafia-related. During that period, new laws were enacted, including the hard prison (41-bis), the dissolution of municipalities for mafia reasons, and the National Anti-Mafia Directorate was created. In Sicily, the first anti-mafia movements linked to civil society spread. In the following years, a downsizing of the Sicilian Mafia was observed, although it was not a definitive defeat so much so that today the main Italian criminal groups, linked to Cosa Nostra, Camorra, and 'ndrangheta, are far from defeated.

Still, the data shows the radical decline in the number of homicides. From 718 Mafia homicides in '91, we are down to 28 in 2019. An impressive drop in just 30 years. With 0.5 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, Italy is the country with the fewest homicides in Europe after Iceland and Slovenia. In Italy today, there are fewer homicides per capita than in Norway, Switzerland or Luxembourg.

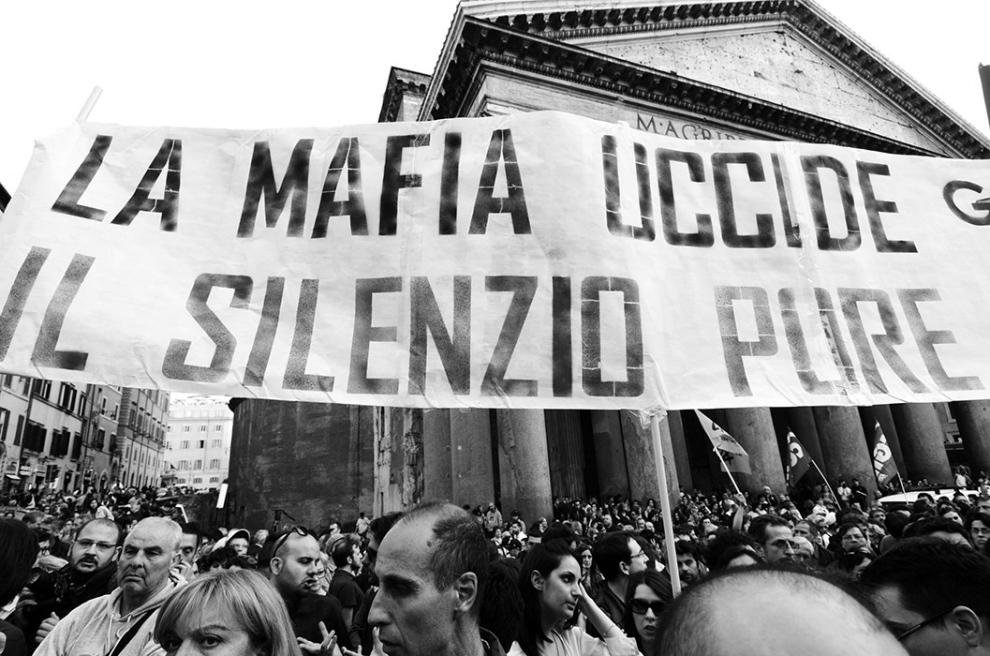

The high levels of violence in the 1980s and 1990s led to strong law enforcement repression and a great deal of media and political attention. Analyzing the RAI archives for the past four decades, and studying the content of national and regional news programs, an interesting trend can be observed. In years with more Mafia murders, Mafia-related media coverage increases, as measured by the percentage of news on the Mafia theme. Conversely, when mafia murders decline, less is said about the topic. This is not just a result in journalism. The same trend can also be seen in speeches in Parliament related to organized crime. For example, in 1992-1994 organized crime was mentioned in 15% of parliamentarians' speeches, 20 years later in only 4.3%.

All this suggests that the decrease in the number of homicides is, at least in part, a strategic choice. This does not imply that violence is no longer used. As reported every year by "Avviso Pubblico", local administrators are the privileged targets of the mafias: threats, threatening letters, arson, assaults. With an average of about one attack per day, this phenomenon goes almost unnoticed in the media, achieving its intended goal: to influence local politics without attracting too much media and political attention. The election period is particularly sensitive: those receiving the most attacks are especially new mayors, immediately after the election, in areas with a greater presence of criminal organizations.

This new strategy actually facilitated expansion into the economic fabric of the country. Since the 1990s, there has been a great growth in the number of businesses and properties seized. In 1991, the state seized 2 businesses and 4 properties from mafias. In 2019, seizures total 351 businesses and 651 properties. Each police operation related to organized crime today leads to seizures of about 1 million euros. In the late 1990s, the average value was about 50 thousand euros.

On the one hand, these numbers indirectly testify to the growth of the economic power of mafia groups, and particularly the 'ndrangheta. On the other, these trends also reflect an increased ability of law enforcement to fight mafia groups where it hurts the most, in economic resources. However, the pessimistic reading is encouraged by other data: in 2019 alone, mafia-related businesses were seized for the first time in 11 new Italian provinces (almost all in northern regions): another sign of the expansion of these groups into new areas of the country.